CNN

—

There were plenty of hugs to go around the tarmac at Joint Base Andrews in Maryland, where three Americans formerly detained in Russia shared emotional reunions with their families.

Late Thursday marked the first time they embraced their loved ones – in many months in two cases and several years in another – since the three were released from Russian detention as part of a historic prisoner exchange.

Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, former US Marine Paul Whelan and Russian American journalist Alsu Kurmasheva were welcomed back warmly at the military facility by President Joe Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris and their relatives.

Gershkovich, 32, who was arrested in March 2023 while on a reporting assignment, was sentenced to 16 years in prison for espionage last month by a Russian court, CNN previously reported.

Whelan, 54, who spent nearly six years imprisoned in Russia following his December 2018 arrest in Moscow while in Russia for a friend’s wedding, received a 16-year prison sentence in 2020 on espionage charges. The US State Department designated both Whelan and Gershkovich as wrongfully detained.

Kurmasheva was handed a six-and-a-half-year prison sentence last month during a closed-door hearing in Russia the same day Gershkovich was sentenced.

Kurmasheva, a Prague-based journalist for the US-backed Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, was detained during a trip to visit her mother in Russia in October 2023 after allegedly failing to register as a foreign agent. She was formally accused of spreading false information last December, CNN previously reported.

The three were among 24 detainees released following a complex, multicountry effort to coordinate a prisoner swap between Russia and other Western nations that spanned years and marked the largest such exchange since the Cold War.

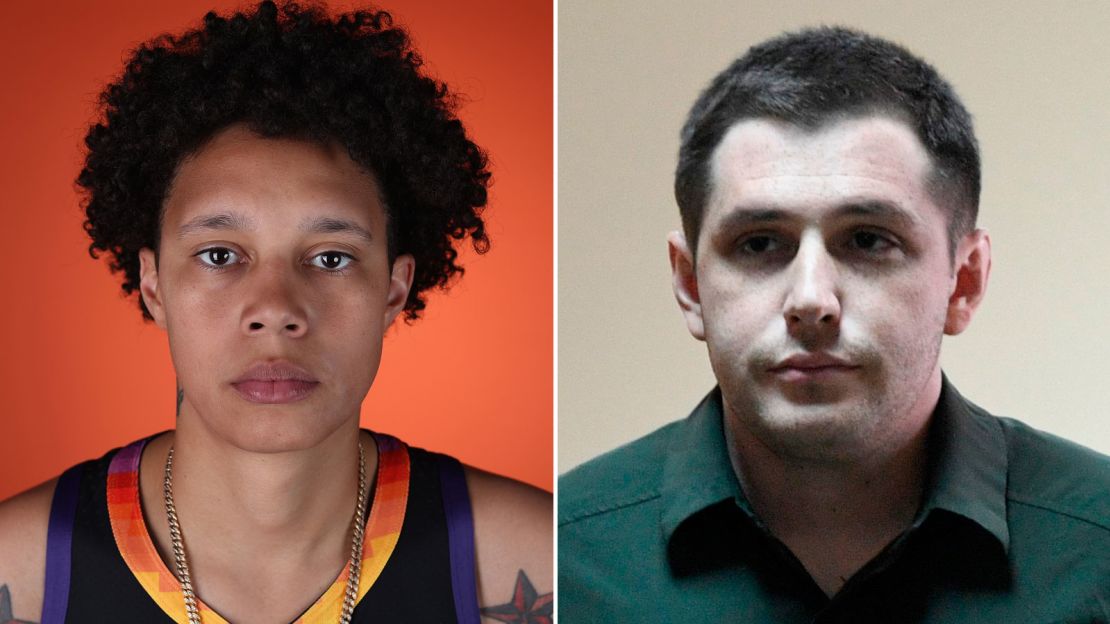

WNBA athlete Brittney Griner, who was released in December 2022 from Russian detainment in a prisoner swap involving Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout, said Thursday she was “head-over-heels happy for the families” of the freed prisoners, The Associated Press reported.

Gershkovich, Whelan and Kurmasheva were later flown from Maryland to the joint base in San Antonio, Texas, where US hostage envoy Roger Carstens told the freed Americans: “ The next phase of your journey begins now.”

The next phase after the media attention winds down, according to former detainees held abroad and one of the organizations working to help current detainees get freed, can be fraught with challenges as people adjust to freedom and a new normal after being held abroad.

Matthew Heath, a former US marine from Knoxville, Tennessee, who was detained in Venezuela from 2020 to 2022, told CNN while he’s “one of the success stories” on his ongoing road to recovery post-release, “there are some returnees who are struggling to this day with mental illness, with job loss.”

Heath, who currently works as a private security consultant and says he’s now “doing great” nearly two years after returning home, added: “It totally disrupts your life … it’s incredibly difficult.”

Here’s what the returnees may face on the road ahead.

After the dust settles

Whelan, Gershkovich and Kurmasheva headed to Brooke Army Medical Center for medical evaluations and additional care for as long as necessary, a US official told CNN.

This is typical protocol for wrongfully detained Americans who return home; Griner also went to the center following her release in 2022.

Upon first returning home, people designated as wrongful detention detainees or hostages by the US government have a choice to participate in a government-run post-isolation program involving mental and physical health checks, said Liz Cathcart, executive director of Hostage US.

The non-profit supports detainees and hostages while they’re still held in captivity and after their release back to the US, Cathcart told CNN. The group has provided long-term support to 167 people in hostage and wrongful detention situations, including Heath.

“If they do that, it can last for a couple days to a couple weeks,” Cathcart said.

The tough period for those released can begin after the post-isolation program ends, she said.

“What happens after they are back in their hometown after this program, or if they elect not to, it tends to be quite a quiet time, which can be really challenging,” Cathcart said.

She added: “The news settles, the dust settles, you now have to actually look in the mirror and start to figure out what your life looks like moving forward.”

Readjusting to family life

Jorge Toledo, one of six senior Citgo Corporation oil and gas executives who were detained in Venezuela in 2017, previously told CNN reintegrating after his October 2022 release as part of a prisoner swap was difficult, particularly when it came to reestablishing relationships with relatives.

“I spent almost five years in captivity, so it’s a long time,” Toledo told CNN’s Pamela Brown in December 2022. He shared he had to rebuild relationships with his spouse, children and grandchildren, who “were just babies” when he was detained abroad.

Returnees might return to a different family dynamic than what they were used to, according to Cathcart.

“Having been held for any amount of time, your family back home will have taken on different roles to work for your release, and so starting to learn everything that your family did for you when you were gone can be really overwhelming,” Cathcart said.

Mental health effects can linger, experts say

Not everyone who’s experienced traumatic experiences such as being detained unjustly abroad for long periods of time may develop post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, experts say, but emotional impacts related to what they’ve been through can be typical.

“It’s going to look a little different from individual to individual, but there are some things that we know to watch for,” Arianna Galligher, director of The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center’s Stress, Trauma and Resilience Program, told CNN.

Struggling with sleep, experiencing flashbacks or nightmares and becoming easily startled are common symptoms in the immediate aftermath of such experiences, according to Galligher.

“They might find themselves having a hard time concentrating, they might be a little more irritable than usual (or) have a hard time getting organized,” she said.

In a New York Times Magazine article in May, Griner said began experiencing PTSD symptoms at the end of her first season back with the Phoenix Mercury.

“People say it’s OK to not be OK. But what the hell does that mean? Just cry when I want to cry? Or be angry when I want to be angry? Or does that mean talking about it? Like, I had to figure that out,” Griner told the magazine.

Coming to terms with a new normal back home can pose mental health challenges for returnees, Cathcart said.

“It’s a new life that you’re reentering, it’s a new stage that you have to mentally come to terms with and understand that life will look different – not necessarily worse, but different – than it did before,” she said.

Cathcart added, “The qualities that we’ve seen captives build in hostage situations have been incredibly useful on the reintegration side, and (with) being resilient through the reintegration period.”

‘Almost like you’re coming back from the dead’

The financial burden of being detained abroad for a lengthy period can be significant, as Heath and his family discovered. The former Marine’s family had to sell his home while he was away and his accounts were closed, he shared.

“It’s almost like you’re coming back from the dead,” Heath said. “Your driver’s license expires, financially, you lose hundreds of thousands of dollars and then you come back and you have to start everything over.”

Hostage US helped support him through the mountains of paperwork awaiting him after his return, according to Heath, who said he faced a “plethora of small legal problems” including unpaid bills such as child support for his son, who lives part-time with him.

Heath said he owed back-due payments of about $40,000. “I accumulated this huge debt and it still causes me legal problems to this day,” he said.

Cathcart noted the hostage release included journalists, some of whose work involved reporting in the country they were detained in.

“Their work might look really different moving forward, and that can be not only a huge emotional burden, but also a really practical burden.”

CNN’s Simone McCarthy, Anna Chernova, Nathan Hodge, Jennifer Hansler, Rosa Flores, Colin McCullough and Nouran Salahieh contributed to this report.