CNN

—

Philip Kreycik should have survived his run.

In the summer of 2021, the 37-year-old ultra-marathon runner used an app to plot a roughly 8-mile loop through Pleasanton Ridge Regional Park in California, a huge stretch of parkland threaded with trails.

On the morning of July 10, as temperatures crept into the 90s, Kreycik set off from his car, leaving his phone and water locked inside. He started at a lightning pace — eating up the first 5 miles, each one in less than six minutes.

Then things started to go wrong. GPS data from his smartwatch showed he slowed dramatically. He veered off the trail. His steps became erratic. By this time, the temperature was above 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

When Kreycik failed to show up for a family lunch, his wife contacted the police.

It took more than three weeks to find his body. An autopsy showed no sign of traumatic injuries. Police confirmed Kreycik likely experienced a medical emergency related to the heat.

The tragedy is sadly far from unique; extreme heat is turning ordinary activities deadly.

People have died taking a stroll in the midday sun, on a family hike in a national park, at an outdoor Taylor Swift concert, and even sweltering in their homes without air conditioning. During this year’s Hajj pilgrimage in June, around 1,300 people perished as temperatures pushed above 120 degrees Fahrenheit in Mecca.

Heat is the deadliest type of extreme weather, and the human-caused climate crisis is making heat waves more severe and prolonged. Add humidity into the mix, and conditions in some places are approaching the limits of human survivability — the point at which our bodies simply cannot adapt.

“We’ve essentially weaponized summer,” said Matthew Huber, a climate professor at Purdue University.

Inside a heat chamber

Kreycik had almost everything on his side when he went running on that hot day: he was extremely fit, relatively young and was an experienced runner.

While some people are more vulnerable to heat than others, including the very old and young, no one is immune — not even the world’s top athletes. Many are expressing anxiety as temperatures are forecast to soar past 95 degrees in Paris this week as the Olympic Games get underway.

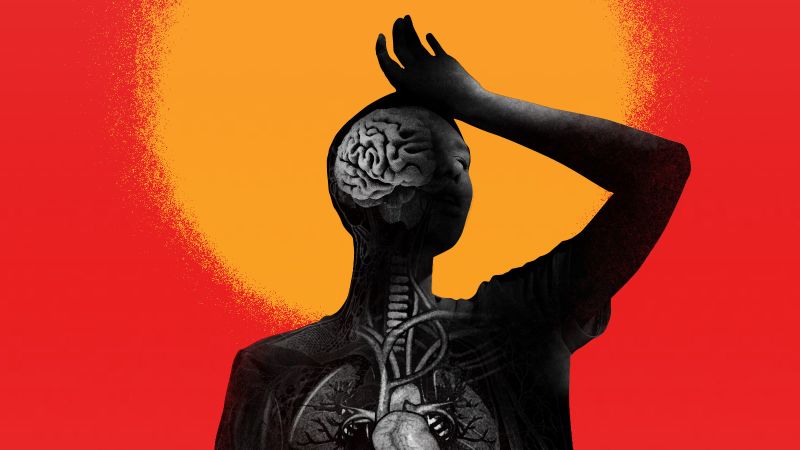

Scientists are still trying to unravel the many ways heat attacks the body. One way they do this is with environmental chambers: rooms where they can test human response to a huge range of temperature and humidity.

CNN visited one such chamber at the University of South Wales in the UK to experience how heat kills, but in a safe and controlled environment.

“We’ll warm you up and things will slowly start to unravel,” warned Damian Bailey, a physiology and biochemistry professor at the university. Bailey uses a plethora of instruments to track vital signs — heart rate, brain blood flow and skin temperature — while subjects are at rest or doing light exercise on a bike.

The room starts at a comfortable 73 degrees Fahrenheit but ramps up to 104. Then scientists hit their subjects with extreme humidity, shooting from a dry 20% to an oppressive 85%.

“That’s the killer,” Bailey said, “it’s the humidity you cannot acclimatize to.”

And that’s when things get tough.

What heat does to your skin

Millions of sweat glands around your body push sweat onto the skin. It transfers heat into the air as it evaporates, which cools you. When it’s too hot and humid, however, it can throw the whole process out of whack.

Too much sweating can make you dehydrated, and your body doesn’t always raise an alarm when it needs more to drink. By the time you feel thirsty, it could be too late — you may be losing fluids faster than you can replenish them.

Very humid heat can cancel out the benefits of sweating. When there is a lot of moisture in the air, sweat evaporates much more slowly, or not at all. Instead, it pools and drips off. Deprived of its main cooling mechanism, your body temperature climbs.

What heat does to your heart