A gargantuan solar flare detected being flung out of the sun on July 23 reached an X14 class, making it the strongest flare of this solar cycle so far.

Thankfully for us, the flare emerged from the other side of the sun and was detected by the Solar Orbiter (SolO) spacecraft orbiting the star.

“From the estimated GOES class, it was the largest flare so far,” Samuel Krucker, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley who works on SolO, told spaceweather.com. “Other large flares we’ve detected are from May 20, 2024 (X12) and July 17, 2023 (X10). All of these have come from the back side of the sun.”

The largest flare of the solar cycle on our side of the sun was an X8.9 flare, which occurred on May 14—the most powerful since 2005 at the time.

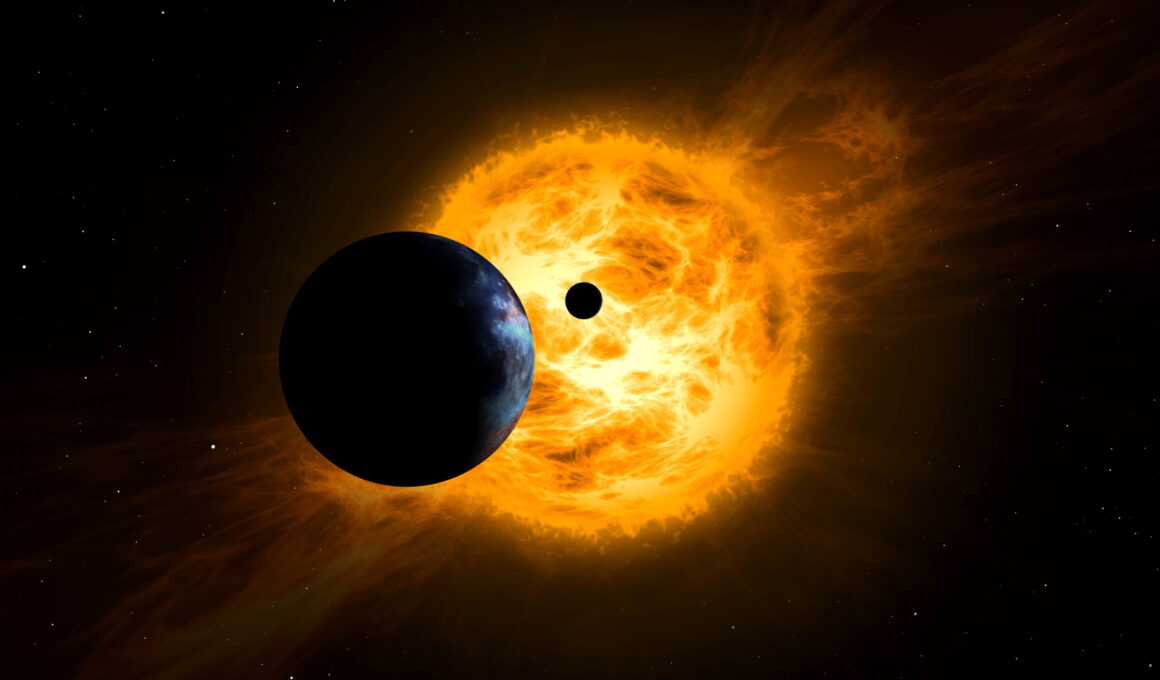

Solar flares are classed into five main categories (A, B, C, M, X), with each class representing a tenfold increase in strength. They are created when the magnetic field lines at active areas on the sun’s surface become increasingly twisted and tangled, eventually breaking and reconnecting in a process known as magnetic reconnection. The energy released during magnetic reconnection accelerates particles and heats the surrounding plasma, causing a solar flare.

The intense radiation from a solar flare can travel at the speed of light, reaching Earth in about eight minutes. This radiation can cause radio blackouts, affect satellite communications, GPS systems, and power grids, and pose a risk to astronauts in space.

Solar flares are often accompanied by coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which are massive bursts of solar plasma and magnetic fields rising above the solar corona and released into space.

“Solar flares are where areas of solar activity (normally seen as sun spots) suddenly realign or shift, throwing off a flare. The amount of energy in an X-class flare can sound scary, but the true impact for us on Earth depends very much on a number of factors,” Alan Woodward, a professor of computer science and space weather expert at the University of Surrey, told Newsweek.

“Some give comparisons of the “Carrington Event” in 1859, which is thought to have released more power than millions of the largest nuclear bombs ever exploded on Earth. However, the chances of a flare affecting the Earth are lessened because the flares pop out in all directions, decreasing the chance of them hitting Earth.”

Solar flares and CMEs are more common as the sun approaches its solar maximum, which is a peak in activity in the middle of each solar cycle. The solar cycle is an approximately 11-year cycle in which the sun’s activity levels vary hugely, with the most recent solar minimum occurring in 2019 and the next solar maximum being due between late 2024 and early 2026.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about solar flares? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.