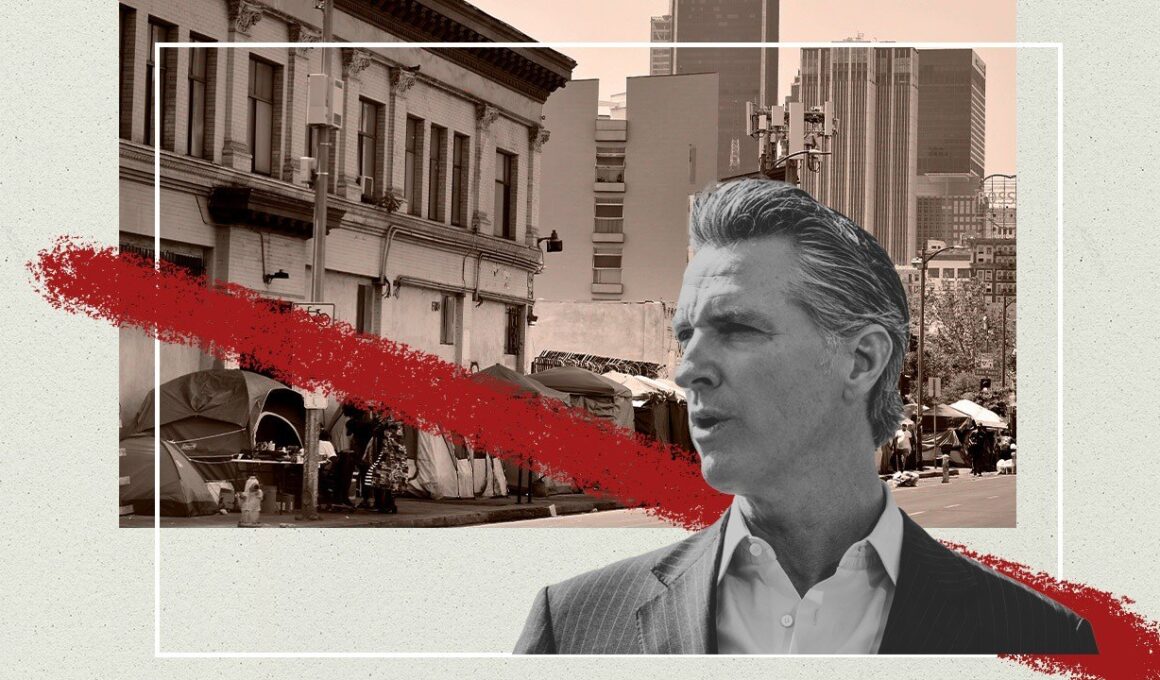

In a sweeping move, California Gov. Gavin Newsom has ordered state agencies to dismantle homeless encampments—but, it will have only a marginal effect on increasing home values, experts say.

The order applies specifically to state agencies and the Department of Transportation, but it gives Newsom leeway to withhold state funds from city and local governments that refuse to comply.

“We must act with urgency to address dangerous encampments, which subject unsheltered individuals living in them to extreme weather, fires, predatory and criminal activity, and widespread substance use, harming their health, safety, and well-being, and which also threaten the safety and viability of nearby businesses and neighborhoods, and undermine the cleanliness and usability of parks, water supplies, and other public resources,” Newsom said in a speech on Wednesday.

The move comes a month after the U.S. Supreme Court issued a controversial ruling giving cities the ability to penalize people for sleeping outdoors.

Newsom praised the ruling for removing the “legal ambiguities that have tied the hands of local officials for years.”

The homelessness crisis in the state has also had a knock-on effect on real estate prices, says University of Illinois-Chicago economist Ryan Bhandari.

Bhandari studied how homeless encampments affected real estate prices in Los Angeles and found that 58% of residential properties sold in Los Angeles between March 2016 and August 2022 had homeless encampments within 0.3 miles of them. These homes were sold on average for 3.14% less than they otherwise would have, a total realized loss of over $2.5 billion across more than 70,000 properties.

On a high level, says Realtor.com® economist Ralph McLaughlin, “things like trash, smells, or fires or unsightly debris, things that build up nearby … homebuyers are willing to pay more to not have that in their front yard.”

(David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

But because this latest executive order applies only to state land, it’ll have a limited effect on the housing market, he adds.

There is very little state-owned land in California’s major cities. The largest amount of state-owned land within major cities is actually freeways—areas that Newsom has already executed clearance plans on.

“If you happen to already live near a freeway that has a homeless encampment, cleaning up the homeless encampments may give you some marginal increase in home value. But your home value is likely to be lower anyway because you live near a freeway,” McLaughlin says.

Newsom, who has been governor since 2019, has made addressing the growing homelessness problem a cornerstone of his platform.

Five of the 10 cities with the highest rate per capita of homelessness are in California: San Francisco, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Sacramento, and Oakland. California has the highest rate of poverty in the country and is also facing a lack of affordable housing, both of which are major contributors to the homelessness crisis in the state.

California has dealt with a homelessness crisis since the 1980s, when the state’s population ballooned from 6 million to 30 million. Between 2010 and 2020, California’s population grew by 5.8% but its housing stock increased only by 4.7%. That’s put a premium on existing housing options and pushed many out of the market.

As rents rise, middle-class people are pushed farther and farther out of urban centers, while low-income people often have nowhere to go.

In cities such as San Francisco, where the median rent is $3,350, and Los Angeles, with a median rent of $2,800, even adequately employed people are scrambling for housing. In 2019, an RV camp sprung up outside of Google’s Mountain View, CA, headquarters, consisting primarily of Google employees unable to find housing.

(Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Around 30% of renters in the state spend more than half of their incomes on rent, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. And according to the U.S. Census Bureau, around 35% of people with monthly rents or mortgages in the state say they’re behind on rent and in danger of eviction or foreclosure—3% higher than the national average.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the problem, creating a tipping point where many who were living on the margins were forced onto the street. For some newly unhoused people during the pandemic, encampments provided a sense of community and security in numbers.

The state also doesn’t have enough beds to accommodate moving unhoused people off the streets. Last year, more than 181,000 people experienced homelessness in California. Of those, around 123,000 people were unsheltered, meaning they were sleeping outside or in cars. But the state has only 71,000 emergency beds.

It may take weeks and months for Newsom’s order to be carried out, and there is resistance among some Californian city leaders.

While San Francisco Mayor London Breed said she supported “ aggressive” handling of the encampments, Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass criticized Newsom’s plan.

“Strategies that just move people along from one neighborhood to the next or give citations instead of housing do not work,” she said in a statement.