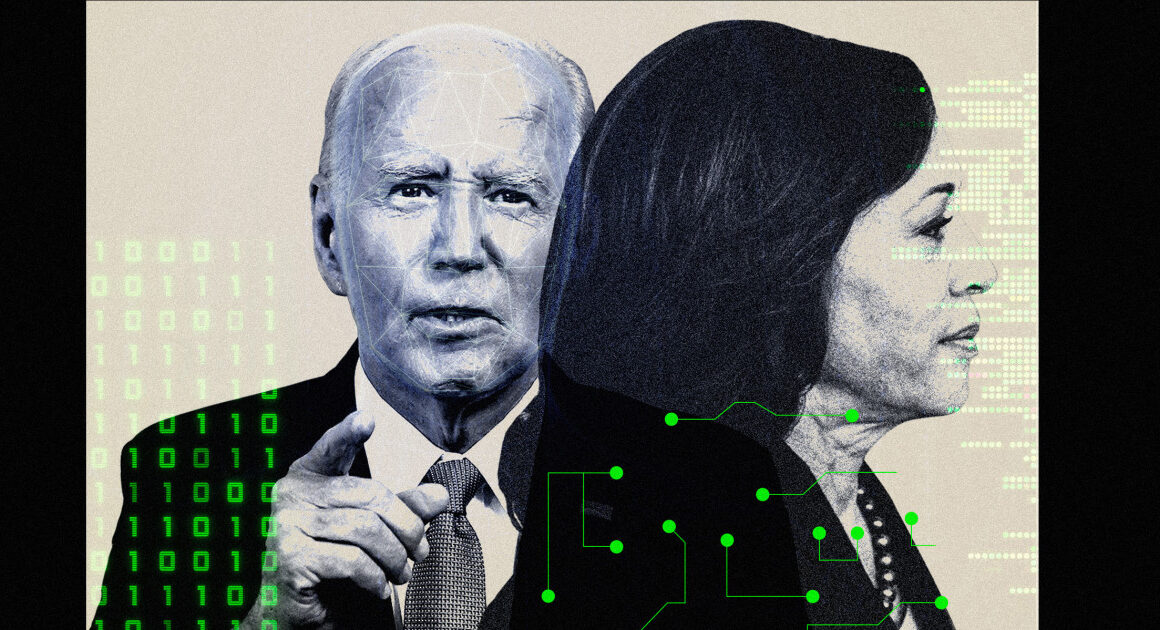

A fake Kamala Harris campaign ad using a manipulated version of her voice has become a flash point in the escalating debate over how to treat manipulated media — often referred to as deepfakes — ahead of the 2024 election.

The fake Harris audio, recirculated by Elon Musk in a post that has been seen more than 150 million times, includes digs about diversity, President Joe Biden and border policies, as well as edited clips from real Harris appearances.

But reactions to the deepfake of Harris have been divided, with some saying it’s an example of a dangerous type of manipulated media that needs tight regulation, and others saying it’s a clear example of parody and thus deserves a different type of treatment.

“This is one of the most prominent political deepfakes to circulate so far, it concerns a major presidential candidate, and the misleading synthetic audio was reposted by the owner of the platform,” Lisa Gilbert, co-president of nonprofit consumer advocacy organization Public Citizen, told NBC News. “The stakes are really high.”

A representative for Harris’ campaign confirmed to NBC News that the audio was fake and that the video was not a real campaign ad.

“We believe the American people want the real freedom, opportunity, and security Vice President Harris is offering; not the fake, manipulated lies of Elon Musk and Donald Trump,” the campaign representative said in a statement.

Other deepfake videos and images, many of which are created with generative artificial intelligence tools, have targeted politicians such as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., with fake sexually suggestive images and pornographic videos, or used their likenesses, including former President Donald Trump’s, to create scam advertisements.

AI-generated images have also depicted Trump running from police and being arrested and were used alongside headlines about his arrest.

But alongside those deceptions, other deepfakes have appeared to be, or have been framed as, satirical political expression, leading to divided reactions.

Ahead of Biden’s address to the nation discussing his decision not to run for re-election, a deepfake video that depicted him cursing and using a slur for gay people was posted on X, where it still remains up with more than 20 million views and no clear label indicating that it is fake. The video included a PBS News logo and a creator watermark.

PBS released a statement debunking the deepfake of Biden, writing: “We do not condone altering news video or audio in any way that could mislead the audience.”

Despite the lack of a label on the Biden deepfake video, many replies said that it was clearly fake and questioned whether a note was even needed to disclose that it was AI-generated.

Many social media platforms, including X, have policies against sharing synthetic and manipulated media in an attempt to misinform audiences. Some posts on X that include deepfakes have been labeled as such by the platform even if the person posting them doesn’t clarify they are manipulated.

X also allows parody accounts, as long as they “distinguish themselves in their account name and in their bio.” The platform does not have specific rules around individual posts that constitute parody. Other major social media platforms, like Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, have a manipulated media policy that doesn’t apply to satire and parody. X doesn’t differentiate between posts that are parody or not in its manipulated media policy.

Deepfakes have largely been met with concern and criticism, being inherently misleading and oftentimes used to harass people, sexually and otherwise. Audio deepfakes have been used in attempts to misinform potential voters, most notably when a robocall in New Hampshire used a deepfake of Biden’s voice to tell registered Democrats not to vote in the state primary. The political consultant behind the call faces criminal charges and a $6 million fine.

The fake Harris ad has inspired similar outcry and criticism, but the content and context of the video are very different from the Biden robocall.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom responded to Musk’s post sharing the video by saying that “Manipulating a voice in an ‘ad’ like this one should be illegal” and adding that he plans to sign a state bill into law that would prohibit it. As many as 18 states have already passed regulations on AI deepfakes in elections, according to Public Citizen’s tracker, and six states have pending legislation. Federal legislation has also been proposed by Sens. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., and Josh Hawley, R-Mo.

The existing state legislation around realistic AI deepfakes used to influence elections varies, with some states, like Texas, making it a criminal offense and others, like Utah, instituting civil penalties. Several of the laws allow AI deepfakes in election materials as long as they are clearly labeled. Some of the laws make specific exceptions for parodies, some only apply to official campaign or PAC materials, and some only apply within 30 days of an election, among other variations.

After speaking out against Musk’s post, Klobuchar said she is re-upping an attempt in the Senate to push through federal legislation that would similarly ban “deceptive deepfakes of federal candidates” and “require disclaimers on AI-generated political ads.”

In a response to Newsom, Musk wrote in part that “parody is legal in America.”

Neither X nor Musk responded to separate requests for comment.

Free speech and civil liberties experts who spoke with NBC News agree that the video should be considered protected speech.

“It’s clear satire or parody,” said Aaron Terr, director of public advocacy at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. “Humor, mockery and exaggeration have long been effective tools for criticizing the powerful and highlighting absurdities in our politics and culture, and the First Amendment recognizes that.”

The fake Harris audio was originally created and posted on YouTube by a conservative content creator with a description labeling it as “significantly edited or digitally generated.” The YouTuber who created the video also prominently labeled it as a parody on X, but Musk’s post does not share any indication that the video is manipulated.

“There’s a question as to whether or not it violated X’s own policies,” said Lou Steinberg, founder of cybersecurity research lab CTM Insights. “The rules are soft at the edges for some people.”

Public Citizen called on Musk to take the fake audio of Harris down and has petitioned the Federal Election Commission to regulate the use of generative AI deepfakes in election ads, on which the FEC remains undecided.

David Greene, the civil liberties director and senior staff attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said that a law against circulating deceptive media would “have constitutional problems.”

“You hate to agree with Elon Musk, but parody is protected speech,” he said, comparing the video to viral hoaxes spread online over the past week about Trump’s VP pick, Sen. JD Vance. Despite the growing sophistication of audio deepfakes, which can easily fool listeners, Greene said “it’s still important to have protection for commentary and parody.”

“Just because there are First Amendment barriers doesn’t mean that other tools aren’t available, like calling this out,” he added.

In addition to using fake audio, the video Musk shared plays on conservative talking points about Harris and Democrats, such as calling her a “diversity hire” for being a woman of color, as well as promoting the conspiracy theory that she is a “deep state puppet.”

Dhanaraj Thakur, research director at the Center for Democracy and Technology, said he would categorize the video as disinformation, “because there is intent to deceive.”

“It incorporates elements of misogyny and racism,” he said. “It follows a playbook that researchers have often observed when it comes to how women candidates, broadly speaking, are treated online.”

In 2022, Thakur authored a research paper that found political candidates in the U.S. who are women of color endure the most severe online abuse, misinformation and disinformation compared to other candidates, based on an analysis of tweets during the 2020 election period.

In the past two weeks, Musk has pivoted to fully endorse Trump and advocate against Harris, using his position as CEO of X and the most-followed person on the platform to push inflammatory rhetoric about the 2024 election.

“If this kind of posting continues, he could individually make an impact in the election that is really significant and severe,” Gilbert said.

While Musk is the most visible person on X, Steinberg noted that foreign entities outside the reach of U.S. laws are also able to post disinformation and deepfakes on the platform.

“There are an awful lot of people who have an awful lot of interest in either creating bias or creating confusion,” Steinberg said. “While this ad may be tongue-in-cheek, we’re at the very beginning of what’s probably going to be our first election with a significant amount of AI-generated disinformation.”

,