CNN

—

The hardline approach Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito takes usually gets him what he wants.

This year it backfired.

Behind the scenes, the conservative justice sought to put a thumb on the scale for states trying to restrict how social media companies filter content. His tactics could have led to a major change in how platforms operate.

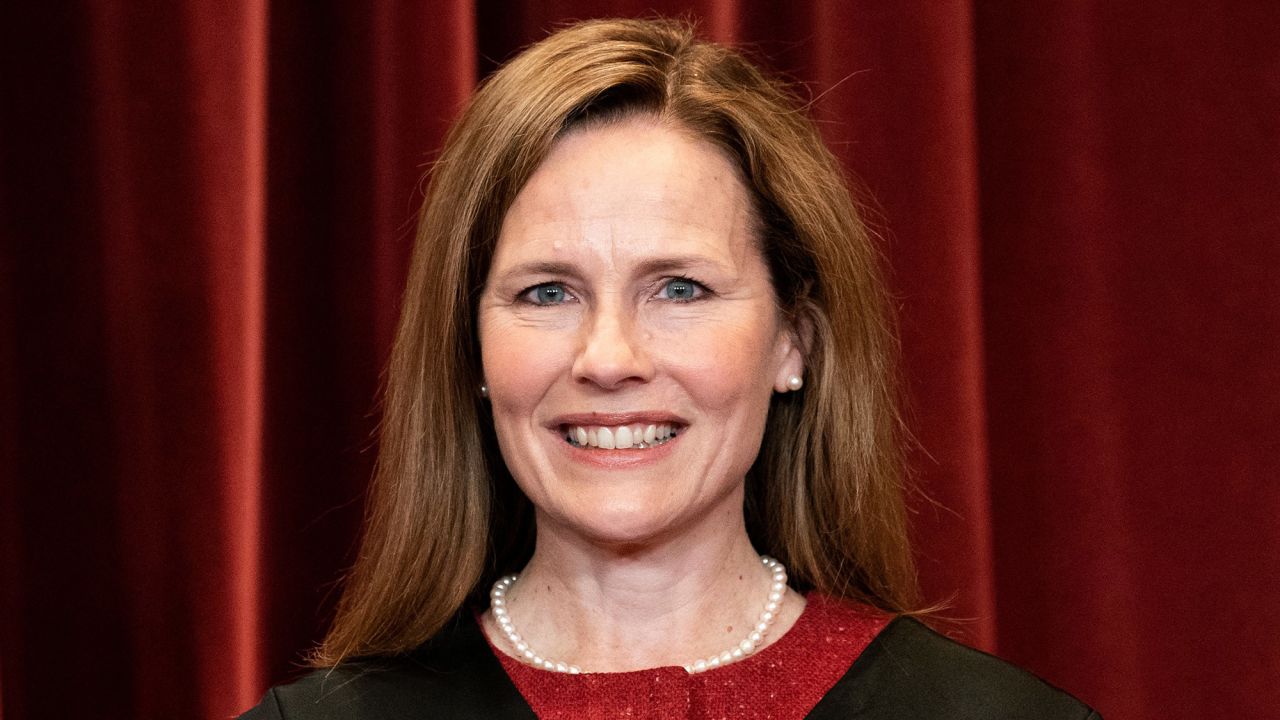

CNN has learned, however, that Alito went too far for two justices – Amy Coney Barrett and Ketanji Brown Jackson – who abandoned the precarious 5-4 majority and left Alito on the losing side.

As a result, the final 6-3 ruling led by Justice Elena Kagan backed the First Amendment rights of social media companies

It is rare that a justice tapped to write the majority opinion loses it in ensuing weeks, but sources tell CNN that it happened twice this year to Alito. He also lost the majority as he was writing the decision in the case of a Texas councilwoman who said she was arrested in retaliation for criticizing the city manager.

Alito has long given off an air of vexation, even as he is regularly in the majority with his conservative ideology. But the frustration of the 74-year-old justice has grown increasingly palpable in the courtroom. He has seldom faced this level of internal opposition.

Overall, Alito wrote the fewest leading opinions for the court this term, only four, while other justices close to his 18-year seniority had been assigned (and kept majorities for) seven opinions each.

His unique year in chambers was matched by the extraordinary public scrutiny for his off-bench activities, including lingering ethics controversies and a newly reported episode regarding an upside-down flag that had flown at this home in January 2021, after the pro-Donald Trump attack on the US Capitol. Some of the rioters waved inverted flags that became a symbol of Trump’s protest of the election results giving Joe Biden the presidency.

After The New York Times reported on the flag in May, Democratic members of Congress called for Alito to recuse himself in Trump-related cases. Alito declined, in a letter that explained that his wife had hung the inverted flag in response to a nasty confrontation with a neighbor.

Alito declined CNN requests for an interview.

This exclusive series on the Supreme Court is based on CNN sources inside and outside the court with knowledge of the deliberations.

Split rulings from Trump-nominated judges divided SCOTUS

The Texas and Florida disputes grew from conservative claims that their viewpoints were being censored online by Facebook, Twitter (now known as X) and other platforms.

The states enacted their laws in 2021 and, with variations, restricted the ability of social media platforms to filter third-party messages, videos and other content. The laws were passed a few months after Facebook and Twitter removed Trump from their platforms, in the wake of the Capitol attack.

When Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed that state’s measure, he said, “there is a dangerous movement by social media companies to silence conservative viewpoints and ideas.” In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis declared in a statement, “If Big Tech censors enforce rules inconsistently, to discriminate in favor of the dominant Silicon Valley ideology, they will now be held accountable.”

NetChoice, an internet trade association, brought lawsuits in both states, saying the laws broadly violated the First Amendment rights of social media companies. US district court judges in Florida and Texas temporarily blocked the laws from taking effect.

As Texas appealed, the 5th US Circuit Court of Appeals, known for its own right-wing streak, said the platforms’ content-moderation activities did not rise to “speech” that would be protected by the First Amendment.

US appellate Judge Andrew Oldham, a former Alito clerk, belittled the “large, well-heeled corporations that have hired an armada of attorneys from some of the best law firms in the world to protect their censorship rights.”

The 11th US Circuit Court of Appeals, however, ruling on the Florida law, took the opposite tack and declared that content moderation implicated the First Amendment and protections for “editorial discretion.” Writing that decision, US appellate Judge Kevin Newsom said, “‘content-moderation’ decisions constitute protected exercises of editorial judgment.”

(Newsom and Oldham were both appointed by Trump, who also has often complained of online censorship.)

When the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the paired appeals on February 26, the justices struggled with multiple threshold issues, including how the laws might apply to typical social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube, as well as to sites and apps like Etsy and Uber. NetChoice had brought a broadscale challenge, arguing that the laws were unconstitutional in all situations, rather than pointing to specific cases where free-speech rights were violated.

A few days later, as the justices met in private on the dispute, they all agreed that NetChoice’s sweeping claims of unconstitutionality had fallen short and that the two cases should be sent back to the lower courts for further hearings.

The justices, however, split over which lower court largely had the better approach to the First Amendment and what guidance should be offered for lower courts’ further proceedings.

Alito, while receptive to the 5th Circuit’s opinion minimizing the companies’ speech interests, emphasized the incompleteness of the record and the need to remand the cases. Joining him were fellow conservatives Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch and, to some extent, Barrett and Jackson.

On the other side was Kagan, leaning toward the 11th Circuit’s approach. She wanted to clarify the First Amendment implications when states try to control how platforms filter messages and videos posted by their users. She was generally joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Brett Kavanaugh.

Alito began writing the court’s opinion for the dominant five-member bloc, and Kagan for the remaining four.

Alito goes too far and Barrett flips

But when Alito sent his draft opinion around to colleagues several weeks later, his majority began to crumble. He questioned whether any of the platforms’ content-moderation could be considered “expressive” activity under the First Amendment.

Barrett, a crucial vote as the case played out, believed some choices regarding content indeed reflected editorial judgments protected by the First Amendment. She became persuaded by Kagan, but she also wanted to draw lines between the varying types of algorithms platforms use.

“A function qualifies for First Amendment protection only if it is inherently expressive,” Barrett wrote in a concurring statement, asserting that if platform employees create an algorithm that identifies and deletes information, the First Amendment protects that exercise of editorial judgment. That might not be the situation, Barrett said, for algorithms that automatically present content aimed at users’ preferences.

Kagan added a footnote to her majority opinion buttressing that point and reinforcing Barrett’s view. Kagan wrote that the court was not dealing “with feeds whose algorithms respond solely to how users act online – giving them the content they appear to want, without any regard to independent content standards.”