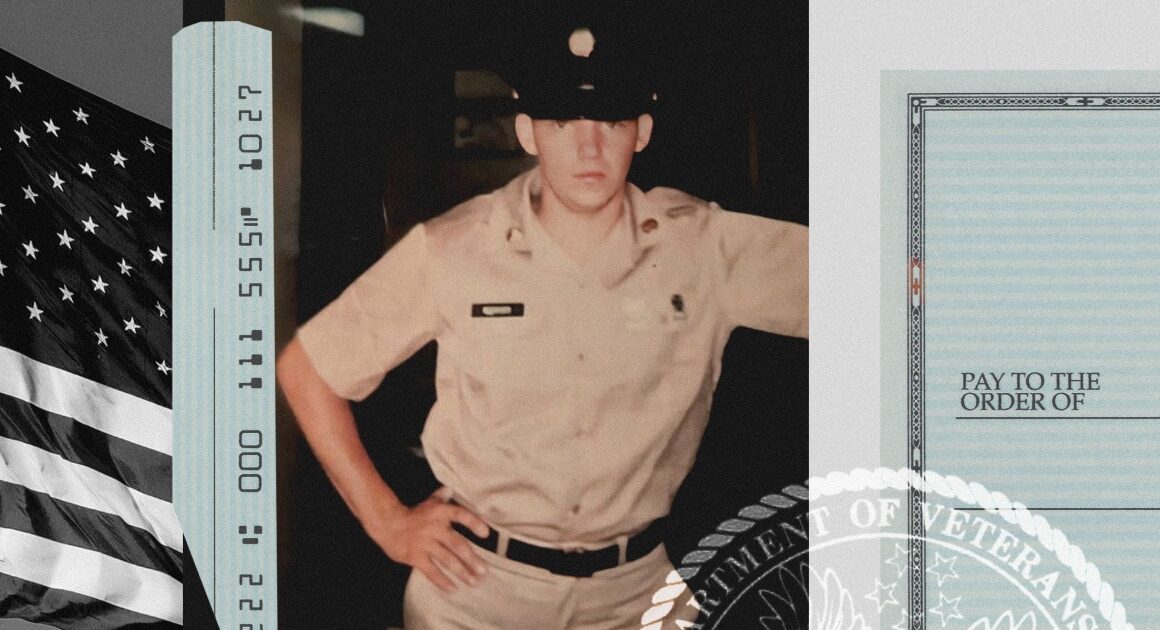

Vernon Reffitt got $30,000 to leave the Army in 1992. It was a one-time, lump-sum special separation benefit offered to service members when the U.S. had to reduce its active-duty force.

Now, more than 30 years later, the federal government wants that money back.

In May, the Department of Veterans Affairs began withholding the monthly disability compensation payments that Reffitt had been receiving for three decades until he repays the $30,000. It would take the 62-year-old nearly 15 years to do so.

“That’s wrong,” said Reffitt, who lives in Twin City, Georgia. “You can’t just up and take it back.”

Thousands have found themselves in Reffitt’s position due to a little-known law that prohibits veterans from receiving both disability and special separation pay. Under the law, the VA has to recoup special separation benefits from veterans before those eligible can begin receiving disability payments.

The law has forced at least 79,000 veterans to repay different types of separation benefits between 2013 and 2020, according to a study published in 2022 by the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit research group. The actual number of affected veterans is likely much higher because researchers were not able to access data prior to 2013 due to VA system changes, Stephanie Rennane, the study’s lead author, said.

In 2023 alone, the VA said it had to recoup separation pay from nearly 9,300 veterans.

“I think it’s likely that we’re missing a good number of people,” Rennane said. “We don’t have any way of knowing how big it is.”

In Reffitt’s case, the VA erroneously allowed him to receive both benefits without penalty for more than 30 years. In a statement, the agency said it was “unaware of the amount” of Reffitt’s special separation benefit when he began receiving disability compensation in 1992.

The VA said it should have followed up on attempts to determine the separation amount and initiated recoupment earlier. It said it caught the error recently when Reffitt filed a claim under the PACT Act, a law enacted in 2022 that expanded benefits to millions of veterans exposed to toxic substances.

‘Two separate buckets of money’

Certain types of separation payments were offered to active-duty service members in an effort to reduce manpower in certain career fields. The Special Separation Benefit ( SSB) that Reffitt received was primarily offered during the 1990s, officials said.

When veterans apply for disability compensation, the VA said the form they use states that separation pay may be recouped from VA benefits. But it’s too late by then, said Reffitt and two other veterans who spoke to NBC News. The veterans said they were not aware of the law that prohibits both benefits when they took the payout.

Army veteran Daphne Young said she would not have taken the separation pay had she known.

Young, 36, who lives in Columbus, Georgia, said she did not particularly need the extra money when she left the military in 2016. She said the $15,000 lump sum allowed her to take a break from working and volunteer with the Red Cross for eight months.

The shock came in April when the VA notified Young that it would begin withholding her monthly, untaxed disability payment of about $3,700 until she recoups her separation pay.

Young, who is now fully disabled and does not work, crumpled at the thought of losing her only income, which she had been receiving for years.

“It was agonizing,” said Young, a former Army ammunition specialist and combat medic who was deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.

Advocates say the law not only blindsides veterans, but it robs them of earned benefits that should not be linked financially.

While special separation pay is based on a service member’s military career, disability pay solely relates to illnesses or injuries sustained during service, according to Marquis Barefield, an assistant national legislative director with DAV, an advocacy group formerly known as Disabled American Veterans.

“The two payments have nothing to do with each other,” Barefield said. “They are two separate buckets of money.”

Veterans have had an average of $19,700 to $53,000 withheld for recoupment, the RAND study found. The recoupment amounts are the lump sums received after taxes.

It took the legs from right underneath me.

Shane Collins, a Marine veteran

Shane Collins said it took him about 36 months to repay the roughly $33,000 separation benefit he received in 2014 when he left the Marines and when his son was born. “It took the legs from right underneath me,” he said.

Collins, 41, of Twin Falls, Idaho, said he worked at the Pentagon in 2012, focusing on personnel administration, including paperwork and pay. He said he was so familiar with the Defense Department’s manual that he called it his Bible.

Still, he said he did not know he would have to repay his separation benefit if he was granted disability. “I thought they were completely separate, and that’s how it was explained to me as well,” he said.

In 2022, Rep. Ruben Gallego, D-Ariz., introduced a bill that would change the recoupment law. The VA said it does not comment on pending legislation.

While the RAND study published that year was required by Congress following concerns for veterans, the legislative progress has been slow.

“It is costly,” Gallego said, “and that’s kind of been the biggest hindrance of why I can’t get it through.”

Under the law, veterans have a chance to pursue a waiver of their recoupment responsibilities for voluntary separation pay, but the standards are high. To get a waiver, the VA said the secretary of the applicable branch of service must determine that “recovery would be against equity and good conscience or would be contrary to the best interests of the United States.”

Young did not receive a waiver. But with the help of the DAV advocacy group, she was able to reduce the monthly amount withheld, although that means it will take her longer to repay the VA.

“There has to be a better way,” she said.

Reffitt, who was deployed to Panama and Honduras and did two tours in Germany during his service as a military policeman from 1979 to 1992, is still working out a plan.

In the meantime, Reffitt, who also supports his wife, has tightened his budget by reducing the number of medical appointments he used to have regularly scheduled to manage his mental health, knee injury and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“I’ve already canceled a couple appointments,” he said.

,