Something in the water? Why we love shark films

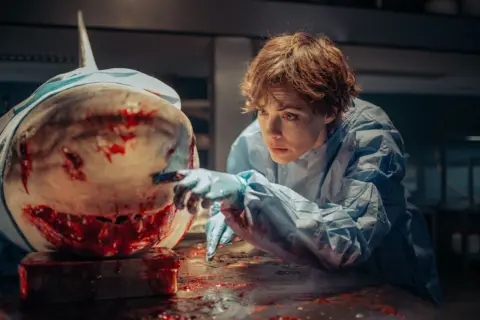

StudioCanal

StudioCanalFrom the Steven Spielberg classic Jaws, to predators stalking the Seine in Under Paris, there is no shortage of shark films.

Hollywood and audiences love them, seemingly never tiring of the suspense, gore and terror.

There are prehistoric giant sharks in The Meg, genetically engineered ones in Deep Blue Sea, and sharks high on cocaine in the ingeniously named Cocaine Shark.

Even Donald Trump is a fan – he was reportedly due to play the US president in a Sharknado film, before becoming the actual president.

I became hooked on them after watching James Bond film Thunderball, where the villain keeps sharks in his swimming pool.

It led to a lifelong interest in shark films, as well as an irrational fear of swimming pools, even ones filled with chlorine inside leisure centres.

Hayley Easton Street is the British director behind a new shark film, Something in the Water, which tells the story of a group of women stranded at sea.

She explains that, as fan of shark films herself, she “absolutely wanted” to make the movie.

So shy are shark movies so popular? “It’s the fear of what could be going on with the unknown of [the sea],” she tells BBC News.

“Just being stuck in the middle of the ocean is scary enough. You’re trapped in something else’s world and anything could happen.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesForensic psychologist Professor Susan Young agrees that the fear of “the unknown, being alone and helpless” is powerful.

She says watching terrifying shark films in the comfort of your own home or in the cinema “allows you to confront your fears without real danger… and release pent up emotions in a safe and controlled environment”.

Prof Young adds: “It means people can face the boundaries of human behaviour and by viewing extreme content they’re testing their own limits and boundaries… and that emotional release is a form of catharsis.”

She explains that Sigmund Freud’s theories apply as, “from a psychodynamic perspective, these films tap into unconscious fears and desires and provide this safe outlet for exploring repressed emotions and instincts such as aggression and the fear of death”.

Netflix

Netflix‘We strapped a fin to a diver’

Making Hollywood sharks look like the real thing can be a challenge.

The production of Jaws was marred by malfunctioning mechanical Great Whites – one sunk and they were corroded by the ocean’s salt water.

The lead actors spent long periods sitting around, waiting for a prop shark to be fixed.

Director Steven Spielberg told the BBC’s Desert Island Discs in 2022 that the debacle actually led to a “much better movie” because he had to be “resourceful in figuring out how to create suspense and terror without seeing the shark itself.

“It was just good fortune that the shark kept breaking,” he said. “It was my good luck and I think it’s the audience’s good luck too because I think it’s a scarier movie without seeing so much of the shark.”

Street says they were working with a limited budget on the set of Something in the Water, so the team came up with an ingenious solution.

“We made a tiger shark fin,” she recalls. “We had this brilliant diver, Baptiste, who could hold his breath for a really long time.

“So we strapped this fin to him and gave him an underwater scooter which he could drive approximately at the speed of a shark.

“It was brilliant because it meant the actors actually had a shark fin to react to, so it allowed them to feel what it would be like if you did have these sharks circling you.”

Warner Bros

Warner BrosBut despite Street’s love of shark films, she did not want the ones in hers to be portrayed as marine serial killers.

“We kill 100 million sharks every year,” she notes.

The director was also aware that the release of Jaws led to a huge rise in the hunting of sharks, partly because they had been portrayed as merciless killers.

“As much as I love shark films, I love sharks.

“I was really conscious of that, because it’s easy for people to start seeing them as killing machines… or monsters, which they are not.”

She adds: “I feel it’s more scary to have the realistic theme of it, that, you know, if you are out in the ocean and there are sharks and they do mistake you for something else, they will kill you.”

Despite the huge success of Jaws, Spielberg has said he “truly regrets the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film”.

‘A huge problem for conservation’

Allow Instagram content?

and

before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Spielberg is not the only person concerned about Hollywood’s portrayal of sharks and the impact it continues to have.

US marine biologist Andriana Fragola dedicates herself to educating people about sharks, often sharing videos of her diving with them.

She says they are “misunderstood predators” that have been harmed by movies and the media.

Andriana tells me that she has watched Netflix’s new shark film, Under Paris, and was not impressed.

“Their whole thing was it’s about conservation, about studying them, but then the sharks are still eating people.

“So it’s giving a little bit more of a rounded education and a little bit more depth to the story, it’s not just people swimming at the beach and getting attacked and eaten.

“But the bottom line and what people can draw from the movie is that sharks are still really dangerous to people and they’re just going to continuously hunt and eat people.

“If that was true, we would be reduced as a human species. Everyone who goes to the beach, they would be threatened.”

The director and co-writer of Under Paris, Xavier Gens, says he is also an environmentalist.

He told The Hollywood Reporter that, while the danger in Jaws is the shark, he wanted to “highlight the perils of human greed” in his movie.

Andriana says the perception of sharks causes a real issue for conservation.

“It’s a huge problem because people don’t want to protect something that they’re scared of.

“The perception from people is that they’re dangerous to humans so we should eradicate them, and that’s obviously a huge problem for conservation and getting people to want to empathise or sympathise with sharks and wanting to actually protect them.

“It’s unfortunate because 100 million sharks are killed every year, and globally sharks kill fewer than 10 people every year.

“We’re really focused on the sharks being the monsters and them being out to get us. In reality it’s the opposite.”

It is unlikely that Hollywood will stop making shark films, or we will stop watching them.

But the figures show that far from being the serial killers of the sea, sharks are actually much more likely to be the victims of humans.