China is currently leading the gold medal tally at the Paris Olympics with the US – largely thanks to the impressive abilities of its swimmers and divers, powering to victory in event after event.

But for many acquainted with China’s recent sporting history in the water, all that glitters may not be gold.

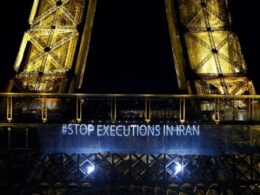

Earlier this year, it emerged more than a third of the 31 swimmers in China’s Paris team were among those who’d previously tested positive for a banned performance-enhancing heart drug, trimetazidine (TMZ).

Then, only days before the Paris games started, the US media exposed another Chinese doping scandal, this time involving two swimmers who tested positive in 2022 for a powerful but outlawed anabolic steroid.

But China’s athletes are hardly the only ones who’ve been accused of doping. An anonymous poll of competitors at the 2011 World Athletics Championships found nearly 44 per cent of supposedly ‘clean’ athletes had used banned supplements in the previous year. (As of 2020, Russia tops the list for violations.)

Critics say the Enhanced Games are really about selling the drugs and other products fuelling the booming anti-ageing industry

But what if there was an alternative Olympic Games where cheating won’t happen simply because it won’t be possible. At the Enhanced Games, which may start as early as next year, the use of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) will not only be legal but actively encouraged.

The Enhanced Games is the dream child of a group of self-assured, wealthy venture capitalists and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. The competition will focus initially on five key sporting categories: track and field, swimming, weightlifting, combat sports and gymnastics.

Unlike the Olympic Games, participants will be paid to compete, with those who break world records eligible for million-dollar prizes. Each of the ten athletes picked to be the ‘faces’ of the games will get $100,000 (£78,000).

Organisers have yet to reveal exactly what they will and won’t permit but – aside from the drugs – possible mechanical enhancements that have been mooted range from bionic implants to AI glasses that tell a javelin thrower how to maximise the length of their throw.

The man behind the Enhanced Games, Australian lawyer and businessman Aron D’Souza, says the goal is to harness science and medicine to ‘elevate humanity to its full potential, through a community of committed athletes’.

He claims his idea has implications far beyond sport, recently telling an interviewer: ‘Imagine if a 60-year-old was breaking Usain Bolt’s world record. That would force us to think about what it means to retire at 65. It would be one of the most powerful social signifiers in history.’

This sort of lofty rhetoric has attracted financial support from deep-pocketed backers such as billionaire PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel, a controversial libertarian who has regular blood transfusions from 18-year-old donors in a bid to further his plan to ‘live forever’. A documentary series about the Enhanced Games is also in the works to be produced by a joint venture between Gladiator director Ridley Scott and Tinseltown entrepreneur Rob McElhenney, who jointly bought Wrexham football club with actor Ryan Reynolds.

Widespread illegal doping, say the Enhanced Games’ creators, has made a mockery of events like the Olympics – D’Souza has dismissed the games as ‘hypocritical, corrupt and dysfunctional’ – so why not give every competitor a more level playing field by allowing everyone to do it?

Not surprisingly, the sports establishment has reacted with a mix of horror and contempt to what many clearly regard as nothing more than a grubby little money-making venture that can only damage the wider reputation of sport.

Critics say the Enhanced Games are really about selling the drugs and other products fuelling the booming anti-ageing industry – centred on Silicon Valley – for which the competitors will serve as super-powered human billboards.

Enhanced Games co-founder, German billionaire Christian Angermayer, told Forbes recently: ‘I look at the world through the lens of ‘What’s the business model, or how can we make money?’ ‘

Forbes reports that the London-based company behind the games is in talks to raise £230 million in funding. The World Anti-Doping Agency calls the Enhanced Games ‘dangerous and irresponsible’, while Sebastian Coe, president of World Athletics, was rather more blunt: ‘Well it’s b******s, isn’t it? I can’t really get excited about it.’

He added: ‘There’s only one message and that is if anybody is moronic enough to feel that they want to take part in that, and they are from the traditional, philosophical end of our sport, they’ll get banned and they’ll get banned for a long time.’

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that Team Enhanced Games has been cagey about which top athletes have so far signed up to compete. Only one, ex-world champion swimmer James Magnussen of Australia, has announced he wants to take part.

D’Souza has offered to pay Magnussen $1million (£780,000) if he breaks the 15-year-old world 50-metre freestyle record. Magnussen has said he’s ready to ‘juice to the gills’ to become the fastest swimmer in history.

According to D’Souza, more than 900 athletes have expressed interested in competing, including at least six world record holders and a Team GB medal winner from the Tokyo Olympics.

Another key criticism of the Enhanced Games is that it’s dangerous, as many of the banned drugs that are likely to be involved carry significant health risks, including addiction and even death. At least one senior sports official has already predicted the games will end in deaths.

However, organisers insist the games won’t be a drug-taking Wild West and competitors will take their PEDs under ‘clinical supervision’. Not every drug will be allowed, they say, although their list of acceptable stimulants has yet to be announced.

Sports world sceptics doubt the dopers will be prepared to limit their drug consumption or whether the games organisers will be able to stop them.

Even the Enhanced Games’ own medical advisers have poked holes in some of its most ambitious claims. Asked about Aron D’Souza’s boast about a doped-up 60-year-old running faster than champion sprinter Usain Bolt, Dr Michael Sagner from King’s College London, said his tendons would snap.

Indeed, critics take issue with everything from its ‘ethically bankrupt’ and ‘grotesque’ concept to its organisers’ pretentious and po-faced claims.

The Enhanced Games website, for instance, argues that words like ‘steroid abuser’ and ‘cheating’ are ‘discriminatory language’, while ‘doping’ is ‘colonialist’ and ‘steeped in racial prejudice’ as – so it claims – black athletes are disproportionately accused of doing it.

Although some counsel that, however obnoxious it all sounds, this could be the future of sport, it remains to be seen whether the Enhanced Games will ever manage to get off the ground – with or without performance – enhancing drugs.